Urban Renewal Information |

How Tax Increment Financing Works by Randal O'Toole

To obtain TIF funds, a city (or, in most states, a county) must draw a line around an area it wants to redevelop and that is what becomes the urban renewal district.

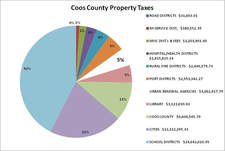

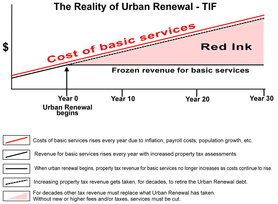

At the time the TIF district is created, the property taxes generated by that area become the base taxes, and those taxes will continue to fund schools and other services for the lifetime of the district. But from that day forward, any increases, or increment, in taxes—whether from new development or from the increased value of existing land and developments—are retained by the urban-renewal agency for redevelopment.

Once existing structures are cleared, most cities also use TIF funds to make improvements within the district. Cities often build infrastructure such as streets, sidewalks, parks, sewers, water, and parking garages— infrastructure that developers would normally pay for themselves. The city then sells the land to developers, typically for far less than the city has invested.

Some states limit the amount of land a municipality can put in a TIF district. Oregon, for example, allows cities to put no more than 25 percent of their land area in a TIF district. Other states have no limit, and cities such as Mission Viejo, California; Port Richey, Florida; and Wheaton, Illinois, have either placed or proposed to place all land within their city limits in a TIF district—effectively claiming (since those states all have blight requirements) that 100 percent of the city is blighted.

In addition to providing funds for redevelopment, TIF districts generally insulate cities from failure. Although most redevelopment agencies are run by boards of directors whose members are identical to the city councils, they are considered separate entities. If a TIF district fails to collect enough incremental taxes to repay its bonds, it can default on the bonds without jeopardizing the city’s bond rating. This allows cities to take on high-risk projects that developers might avoid even if they were guaranteed no increases in property taxes.

TIF agencies get rewarded for inflation. As property values increase due to inflation, TIF revenues rise even if the district does nothing to improve the area. Normally, such increased revenues would be used by schools and other tax entities to offset increased costs, but since the TIF districts are capturing those revenues, other tax districts must either raise taxes or cut back on services.

TIF districts gain when other tax entities persuade voters to increase taxes. Say a school or library district convinces voters to pass a bond levy that increases taxes by $1 for every $1,000 of property value. Taxes are increased both inside and outside of the TIF districts, but the increased revenues inside the TIF districts go to TIF, not to the school or library district.

To obtain TIF funds, a city (or, in most states, a county) must draw a line around an area it wants to redevelop and that is what becomes the urban renewal district.

At the time the TIF district is created, the property taxes generated by that area become the base taxes, and those taxes will continue to fund schools and other services for the lifetime of the district. But from that day forward, any increases, or increment, in taxes—whether from new development or from the increased value of existing land and developments—are retained by the urban-renewal agency for redevelopment.

Once existing structures are cleared, most cities also use TIF funds to make improvements within the district. Cities often build infrastructure such as streets, sidewalks, parks, sewers, water, and parking garages— infrastructure that developers would normally pay for themselves. The city then sells the land to developers, typically for far less than the city has invested.

Some states limit the amount of land a municipality can put in a TIF district. Oregon, for example, allows cities to put no more than 25 percent of their land area in a TIF district. Other states have no limit, and cities such as Mission Viejo, California; Port Richey, Florida; and Wheaton, Illinois, have either placed or proposed to place all land within their city limits in a TIF district—effectively claiming (since those states all have blight requirements) that 100 percent of the city is blighted.

In addition to providing funds for redevelopment, TIF districts generally insulate cities from failure. Although most redevelopment agencies are run by boards of directors whose members are identical to the city councils, they are considered separate entities. If a TIF district fails to collect enough incremental taxes to repay its bonds, it can default on the bonds without jeopardizing the city’s bond rating. This allows cities to take on high-risk projects that developers might avoid even if they were guaranteed no increases in property taxes.

TIF agencies get rewarded for inflation. As property values increase due to inflation, TIF revenues rise even if the district does nothing to improve the area. Normally, such increased revenues would be used by schools and other tax entities to offset increased costs, but since the TIF districts are capturing those revenues, other tax districts must either raise taxes or cut back on services.

TIF districts gain when other tax entities persuade voters to increase taxes. Say a school or library district convinces voters to pass a bond levy that increases taxes by $1 for every $1,000 of property value. Taxes are increased both inside and outside of the TIF districts, but the increased revenues inside the TIF districts go to TIF, not to the school or library district.

Randal O'Toole is a Cato Institute Senior Fellow working on urban growth, public land, and transportation issues. O'Toole's research on national forest management, culminating in his 1988 book, Reforming the Forest Service, has had a major influence on Forest Service policy and on-the-ground management. His analysis of urban land-use and transportation issues, brought together in his 2001 book, The Vanishing Automobile and Other Urban Myths, has influenced decisions in cities across the country. An Oregon native, O'Toole was educated in forestry at Oregon State University and in economics at the University of Oregon. He is a former resident of Bandon OR and well known as The Antiplanner.

|

Click play program on Urban Renewal from The Cato Institute:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Studies on the Effects of Urban Renewal

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

FAQ's About Urban Renewal

What is Urban Renewal?

How does the process of Tax Increment Financing Work?

Where is there a timeline of the Legislative History of Urban Renewal in Oregon?

How does the Property Tax System Work?

What is the Timeline of growth for the US Department of Housing & Urban Development?

What is Urban Renewal?

How does the process of Tax Increment Financing Work?

Where is there a timeline of the Legislative History of Urban Renewal in Oregon?

How does the Property Tax System Work?

What is the Timeline of growth for the US Department of Housing & Urban Development?